Sources and Inspiration

British actress Gertrude Lawrence, 51 years old at the time, was on the lookout for a new work, something to showcase her singing talent along with acting. Her manager approached Rodgers and Hammerstein with Margaret Landon’s “Anna and the King of Siam,” confident that the exotic story of a feisty, Victorian schoolteacher imparting her Western ways on a foreign king would provide a colorful backdrop for a new musical. The partners were hesitant at first; Landon’s book, as well as Anna Leonowens’ memoirs, were unfocused and lacked a clear narrative; instead, they strung together a series of anecdotes, descriptions, and rambling explanations–hardly the cohesive storytelling the composer-songwriter duo were renowned for. Their wives, Dorothy Hammerstein and Dorothy Rodgers, read Landon’s book when it was first published in 1944, and urged their husbands to undertake the story as their next project. It was not until they saw the 1946 film adaptation with Irene Dunn and Rex Harrison, which streamlined Anna’s narrative into a straightforward plot, that they decided to tackle the story.

Creation and Casting

Adapting Leonowens’ tale presented a unique set of challenges. For one, the artistic duo were accustomed to making stars, not fueling the careers of already-established performers; they worried that Lawrence, with her reputation for unprofessionalism and limited vocal talents, would be a problematic leading lady. To compensate, they cast a complete unknown for Anna’s leading man: Yul Brenner (he immortalized the role with his original performance and went on to play the King in revivals throughout his life for more than 4,500 performances).

They also needed to present the world of Siam through song and aesthetics, without coming across as demeaning or prejudiced. Rogers wanted to establish the Eastern-style culture musically, but through an aesthetic style more familiar to American audiences than traditional Thai music. He infused the Siamese songs with an exotic twist, using open fifth and chords in unusual keys, to evoke an Eastern style without overwhelming the audience. These songs contrasted with Anna’s songs, which used more Westernized, conventional harmonic devices. For the non-American characters’ dialogue, Rodgers and Hammerstein conveyed their Thai speech with musical sounds from the orchestra. Instead of inflating the dialogue with thick accents and stereotypes, the King’s style of speech was clipped and emphatic, emblematic of both a cultural dissonance and his own personality.

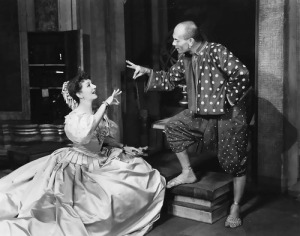

Unlike their previous works, and most of their contemporaries’, the main relationship in The King and I was not romantic. Instead, Anna and Mongkut’s interactions and growth were grounded in mutual understanding and respect. The only romantic song between them, “Shall We Dance?”, was indicative of romantic tensions rather than a star-crossed love affair. The love story, still an integral part of any Broadway musical of the time, found life in the narrative’s subplot between Tuptim and Lun Tha. Their tragic love story was not the thematic nucleus of the musical, however; it served the dual purpose of fueling the audience’s need for an enchanting romance while serving as an example of cross-cultural conflict between Anna and the King’s ideals. In contrast to the glimmering, one-dimensional romantic storylines that most musicals employed, Rodger’s and Hammerstein’s fifth sensation was about abstract ideas and cultural dissonance; neither Anna nor the King were morally good or bad. Rather, they exemplified the murky ethical waters that strangers encounter when breaching an outwardly opposite world.